Kentucky’s appellate and supreme court districts have over-aged, turning from a balanced wine to vinegar after more than four decades in their current iteration.

When lawmakers return in 2022, or possibly even before in a Special Session this year, they will have the task of redrawing the districts to match population shifts over the last decade.

Legislators have made tweaks to trial courts between the different branches of government in recent years, but it has been decades since the last time the judicial maps have been redistricted. Legislators have the constitutional authority to make changes to the appellate court on their own, while changes to the trial courts have been done across the branches of government.

“We haven’t [redrawn] them in four or five decades, so they’re wildly out of whack,” said Rep. Jason Nemes, R-Louisville, when asked about the judicial maps.

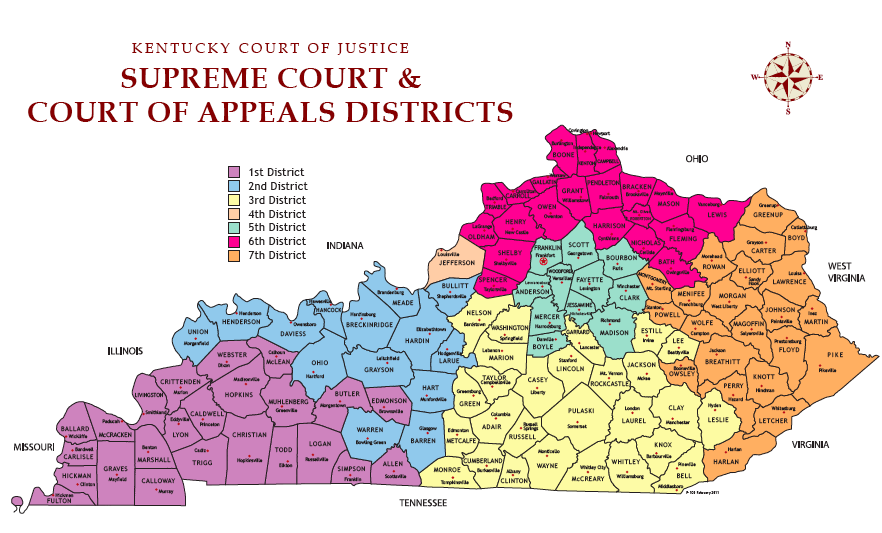

The Court of Appeals districts mirrors the districts for the Kentucky Supreme Court. There are seven districts, and the maps adhere to principles found in the state constitution calling for no counties to be split and the districts need to be nearly equal in representation. The question is still out on the official census numbers, but if it comes back with 4.3 million people living in Kentucky, an equal number of people split between 7 districts would be around 614,000 per district. That’s easier said than done when you can’t split counties.

“Jefferson County is always going to be out-of-whack, because you can’t split counties,” Nemes said.

However, like other regions of the state have grown over the decades they currently have far more people in their districts moving the basis of equal representation. Lawmakers will have to decide if they leave Jefferson County out-of-whack if they make the other six districts that match the correct number of citizens per district. That could mean residents of Jefferson County lose out when it comes to equal justice.

An interesting argument appears, however in equal judicial representation. Judges are elected by people, but they don’t represent people – they are there to uphold the law. So, judges would argue that the rule of districts being nearly equal as possible doesn’t apply to them as strongly as legislative districts apply to those principals for the General Assembly.

The Kentucky Constitution says county lines can’t be split in legislative maps, however, state Supreme Court justices have decided one-man-one-vote principals trump that provision and allow county lines to be split as long as lawmakers split as few counties as possible. Legislative districts are capped at 5 percent plus or minus average population, anything beyond that is unconstitutional on its face. That principle does not apply to the judiciary, judges say. If judges took the same position in judicial maps as they do in legislative maps, Jefferson County with its approximately 766,000 people would have to be split.

There are seven districts, and 14 Court of Appeals judges in Kentucky. Four of those judges are up for election in 2022, then one will be elected in 2024, 2026, and 2028. The cycle repeats with four elected in 2030, and so on.

With four judges being elected in 2022, it’s possible lawmakers would make the new map applicable starting in 2023.

Senate Majority Floor Leader Damon Thayer, R-Georgetown, told Kentucky Fried Politics that he thinks it is highly likely lawmakers will redraw judicial maps in the upcoming session or special session if called by Gov. Andy Beshear.

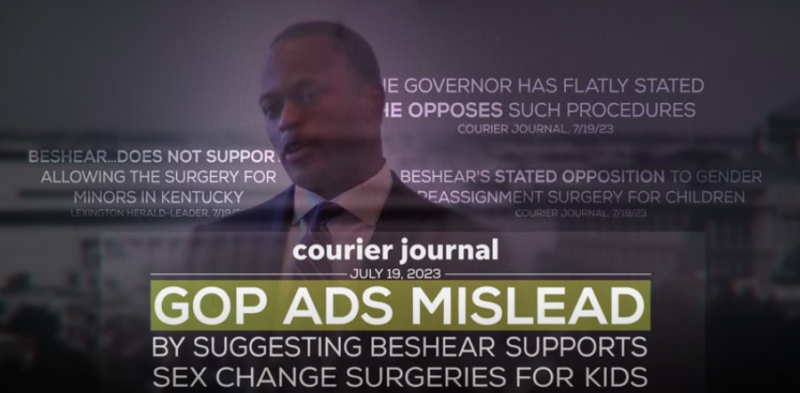

“There’s a lot of animus out there directed towards the judicial branch right now, and a lot of people feel like it’s long overdue,” said Thayer.

Lawmakers have redrawn the judicial districts before, but in tying the maps together in the legislative process the maps were tossed along with unconstitutional legislative maps back in 2012. Upon redrawing the maps in 2013 to meet state Supreme Court muster, Democrats did not adjust the appellate courts.

During the 2012 redistricting process the state Supreme Court drew their own appellate maps, even though that was not required under law, and lawmakers adopted it, Nemes said.

For Thayer there’s also a “bigger question” in mandating how state Supreme Court justices are elected.

“Do we make them partisan, like other states do,” Thayer asked rhetorically? “Do we make them run statewide, but come from a particular district? There are a lot of things on the table, and a desire to make change, but no sort of cohesive strategy for how to get there.”

Whatever lawmakers decide the decision will start with leadership between the House and Senate.

Login

Login  Must include at least 8 charaters

Must include at least 8 charaters