The first time I was in a helicopter, and the first time I covered a race for governor, was the first time I met John Y. Brown Jr.

It was the Monday after the 1979 Kentucky Derby, and Brown was using a helicopter to make up for his late-starting candidacy, choppering from town to town, often joined by his new wife, sportscaster and Miss America Phyllis George. Her celebrity and his money were keys to his election, but the helicopter was a subtle metaphor for his campaign: a strong, fresh wind was blowing.

Brown, who died Monday at 88, made only two promises: to run state government like a business, and to use his sales skills and business experience – from hawking encyclopedias to making Kentucky Fried Chicken an international brand – to bring jobs to our poor state.

For Brown, “run government like a business” meant reform. I doubt he ever used that venerable word to describe his platform, but that’s what it was: Government decisions would be based on business principles, not political alignments, and to do that, he would bring fresh blood into government, including business executives who sneered at politicians.

Brown didn’t have to get specific; voters knew what he meant because of the state’s history of corruption, magnified by investigations of then-Gov. Julian Carroll’s administration, and they knew Brown was running on his own money, not contributions from those who stood to gain or lose at the hands of the state.

The fresh blood included developer Frank Metts, who shook up the Transportation Cabinet and its highway department, a den of political intrigue since its beginning; another Louisville businessman, George Fischer, who as secretary of the Cabinet and rode herd on bureaucrats who tried to hide fat in their budgets; Grady Stumbo, an Eastern Kentucky physician, who ran the huge Cabinet for Human Resources with the poor in mind; Danny Briscoe of Louisville, who brought a political pedigree to the politics-ruined Insurance Department but cleaned it up and published the first comparisons of companies’ rates.

This is not to say that political patronage ended, or that friends didn’t do favors for friends, but Brown wanted no part of it, and set the tone for the executive branch. Outside it, he gave the legislature the independence it demanded and deserved. He often gets more credit for it than he deserves, since any attempt to dictate selection of legislative leaders would probably have failed, but he deserves credit for a battle not fought.

Brown’s critics like to say that he didn’t accomplish much as governor and missed the chance to start Kentucky on the road to school reform, but the state’s economy was mired in a deep national recession, and school reform did follow in the next two administrations. He should be remembered as a reformer in general, one who made Kentuckians realize that their state didn’t have to put up with politics as usual.

In that sense, Brown was a legatee of Louisville’s Wilson Wyatt and Gov. Edward “Ned” Breathitt, whose 1966 legislative session remains the most reformist on record; and his legacy includes at least two other governors.

After another millionaire businessman, Wallace Wilkinson, played politics as usual as governor in 1987-91, Democrats nominated in partial reaction then-Lt. Gov. Brereton Jones, who ran the most openly reformist campaign of any modern governor and won fundamental reforms in campaign finance, elections, government contracting and more. (Jones, 83, is being treated for Alzheimer’s disease, in the care of the Sanders-Brown Center at the University of Kentucky; his wife, Libby Jones, tells me “Our family feels he is receiving excellent care and are eternally grateful for our friend John Y.’s major role in co-founding the center.”)

Jones was succeeded by Democrat Paul Patton, who was a more traditional politician but had a strong reform streak, exercised most strongly in reshaping the state’s higher-education system. His first government job after being a coal operator was in the Brown-Metts Transportation Cabinet.

Kentucky must remember and celebrate these reformers and their reforms, because the reform impulse in Kentucky politics has never been as strong as in most other states – perhaps because Kentuckians are pretty cynical about politicians, and not without cause.

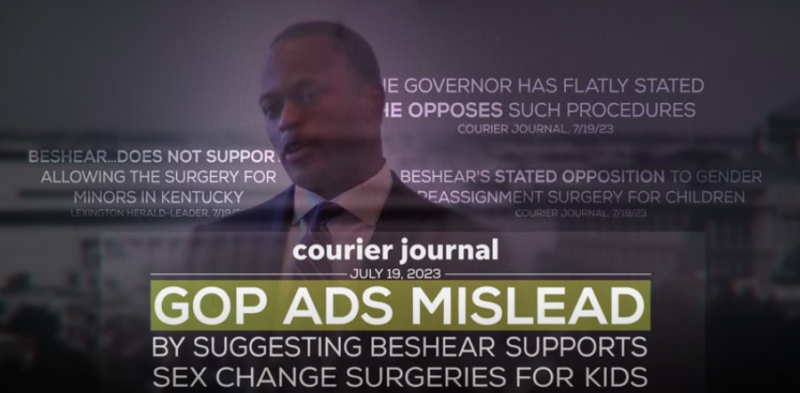

In many communities, they see officials treating public offices as private possessions rather than public trusts, and at the state and federal levels they see the levers of government being worked mainly for the benefit of those who fund the officeholders’ campaigns. Many don’t think their government is on the level, and that’s one reason Donald Trump has millions of supporters; they forgive him for not being on the level because they believe the system is not.

For politics to work, we need doses of real reform, from people like John Y. Brown Jr. May his example be remembered and widely followed.

Al Cross (Twitter @ruralj) is a professor in the University of Kentucky School of Journalism and Media and director of its Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues. His opinions are his own, not UK’s. He was the longest-serving political writer for the Louisville Courier Journal (1989-2004) and national president of the Society of Professional Journalists in 2001-02. He joined the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2010.

Login

Login  Must include at least 8 charaters

Must include at least 8 charaters