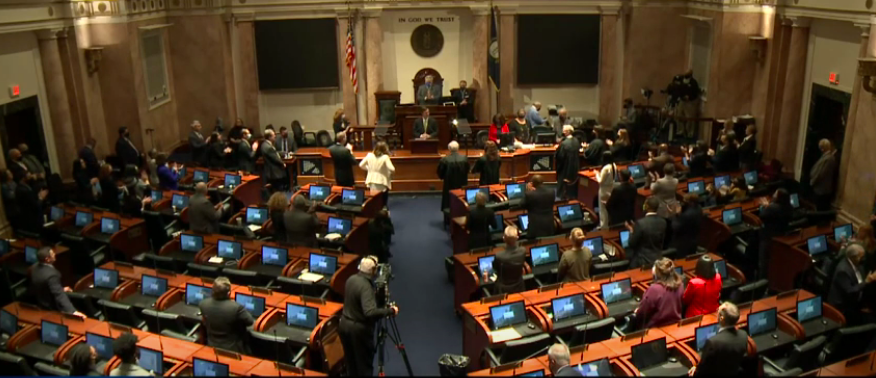

The General Assembly is back in the state capital, and we can safely assume the governor’s not happy about it.

Andy Beshear is a Democrat running for a second term, and the legislature is run by Republicans who want a fellow partisan to replace him. It’s the first time a Kentucky legislature controlled by one party has faced a governor of the other party who is seeking re-election.

He doesn’t like them, they don’t like him, and they’re in a position to cause him trouble.

They can pass legislation that he would be embarrassed to sign or pay a political price to veto. They can spotlight the foibles of his administration, and they can echo and amplify themes of Republicans running to oust him.

Monday, former ambassador Kelly Craft said the state school board and education department “are a mess ― pushing woke agendas in our schools.”

Tuesday, Republican legislators said that’s what the department was doing, and was also driving away teachers, by suggesting students be referred to by their preferred name or pronoun.

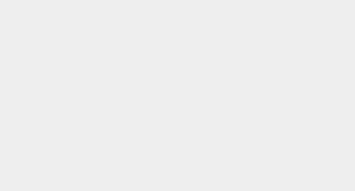

Those two events may have been a coincidence, but it’s clear that Republicans think one way to erode Beshear’s remarkably high poll ratings is with hot-button social and cultural issues.

Last year, the legislature passed a law, over Beshear’s veto, that banned transgender students from competing in women’s sports – an issue that had never arisen in Kentucky schools, and one on which the Kentucky High School Athletic Association had a policy. You can envision the misleading attack ad: “Andy Beshear thinks boys posing as girls should be able to compete in sports against your daughters.” Expect more fear-mongering bills.

Another attack ad could say “Andy Beshear refused to lower your taxes” because he vetoed last year’s bill to cut the state income tax, citing the bill’s expansion of the sales tax to certain services. Republicans overrode the veto, and now they’ve passed the next increment in the income-tax reduction.

The income-tax law seems written with Beshear in mind. It sets up a supposedly automatic process for reducing the tax rate, based on available funds, but also says the cut can’t take effect without legislative action – so the governor will have decide whether to sign it, veto it or let it become law without his signature.

Beshear will also have to keep answering questions about slow delivery of tornado-relief benefits, mis-cut disaster-relief checks (2% of the total, about the Major League Baseball error rate), his administration’s failure to head off big trouble in the Department of Juvenile Justice, and revisionist recriminations about the pandemic prevention measures on which his resilient popularity seems to be built.

Beshear is not without the ability to use the General Assembly for his own purposes. His main proposals for this short session, and apparently his re-election campaign, are a big raise for teachers (stated reason: a teacher shortage, exaggerated but real) and funding universal pre-kindergarten programs.

The legislature is not about to raise the pay of teachers, who are the biggest organized element of Beshear’s political base, and some Republicans see pre-K as invasive social engineering rather than a way of addressing poor children’s educational disadvantages and working families’ need for child care.

Beshear can use those positions against Republicans, and not just to win re-election. If he gets a second term, he could use his proposals and popularity to recruit candidates against incumbent legislators in the 2024 and 2026 elections. That’s what the leader to a political party is supposed to do, but Beshear is a blue governor in a red state and has demurred to conserve his political capital.

The governor has turned one neat political trick on the legislature. When the Senate again refused last year to hear a House-passed bill to legalize medical marijuana, Beshear made a show of gathering public opinion on the issue (we already knew it was overwhelmingly in favor) and issued an executive order with a novel use of his pardon power – prospectively pardoning anyone who had 8 ounces or less of cannabis purchased legally in another state and a doctor’s statement they suffer from one of 21 conditions that cannabis may relieve.

That legal legerdemain left some Republicans sputtering, then arguing over whether the next medical-marijuana bill should start in the House or in the Senate, which seems more logical because that’s where it has failed in the past. If legislators pass something, Beshear can take credit for getting them off dead center. If they pass nothing, he can still say he exercised leadership in the vacuum they left.

Leadership is what voters look for in governors, and in candidates for governor. Beshear’s leadership in the pandemic has given him a lead in the contest, but in Frankfort’s winter baseball game he will likely face some curveballs and brushbacks.

Al Cross (Twitter @ruralj) is a professor in the University of Kentucky School of Journalism and Media and director of its Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues. His opinions are his own, not UK’s. He was the longest-serving political writer for the Louisville Courier Journal (1989-2004) and national president of the Society of Professional Journalists in 2001-02. He joined the Kentucky Journalism Hall of Fame in 2010.

NKyTribune is the anchor home for Al Cross’ column.

Login

Login  Must include at least 8 charaters

Must include at least 8 charaters