LOUISVILLE – With cicadas dropping on parked cars and the laughter of children ringing from the nearby playground at Willow Park in Louisville’s Highlands neighborhood, Louisville Metro Councilwoman Cassie Chambers Armstrong sits at a table surrounded by prominent homes and explains why affordable housing is important in the state’s largest city.

Chambers Armstrong is still in her first year, but already she’s drawing acclaim and is starting to be looked to as a major up and comer in Kentucky Democratic politics.

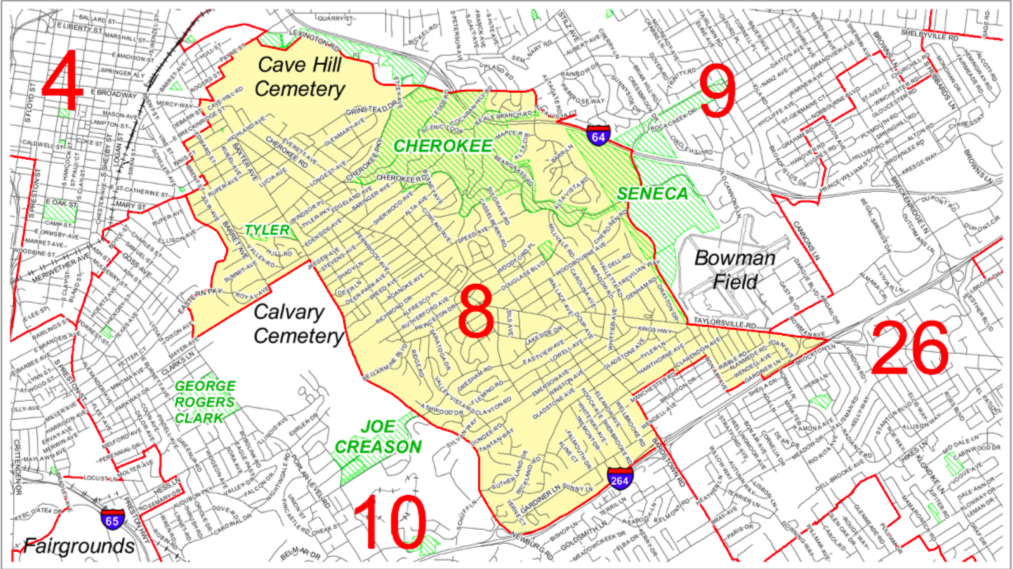

Representing metro district 8, Chambers Armstrong’s council district includes arguably the most influential eight square miles in Kentucky. Louisville Mayor Greg Fischer lives in the district, as does U.S. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell, not to mention the astounding wealth, the lobbyists, consultants, and an entire network of plugged-in constituents.

Stretching from Cave Hill Cemetery in the original Highlands, encompassing Cherokee Park, Tyler Park, and a portion of Seneca Park, the district is bounded by I-264.

Chambers Armstrong has a very different upbringing than many in the Highlands neighborhoods she represents. As detailed in her book Hill Women, Chambers split her childhood between Owsley County, Kentucky, and Berea, Kentucky. Her parents were college students when she was born, and coming home from the hospital, Chambers was brought to a rented trailer in a trailer park in Appalachia. Her mother, one of six kids, a first-generation college student, and a sophomore in college when her daughter was born she decided to stay in school in Berea, and Chamber Armstrong would bounce between grandparents in Owsley County and her mother back at college.

“There was not a lot of money growing up, not a lot of resources, but I really had incredible parents that sacrificed and devoted their lives to being parents and giving me opportunities they hadn’t had,” she said. “We really had a lot of community opportunities, I had great teachers, I took advantage of social services, we were on Medicaid and food stamps when I was growing up.”

Because of the help her family received, it shaped Chambers, seeing government as a “force for good.”

Walking in her mother’s graduation processional with a miniature cap and gown as a child, it was Chambers Armstrong’s mother who drilled into her that education is a ticket to do whatever she wants in this world. Taking the education lesson to heart, Chambers Armstrong went to Yale College, Harvard Law School, and Bellarmine School of Economics as a Fulbright Scholar. Studying neuroscience at Yale, she says she still uses that background to understand how people think and behave in relation to public policy.

However, it was in law school, Chambers Armstrong grew into her own skin and formed her ethos.

“While I was in law school it was when I really came to terms, I think for a long time being at Yale and being at Harvard and being in this sort of privileged educational environments, I was really ashamed of the fact that I grew up poor and that I’d come from a small town in Kentucky and it makes you hide that a little bit to be able to blend in and fit in with a private school crew,” she said. “It wasn’t until I got to law school and started doing poverty law there that I realized how admirable it is when people are struggling and still making ends meet and still fighting for their families, and the dignity of people who work hard without a lot of resources. I think seeing that and feeling that empathy and admiration for my clients really helped me come to terms with my own background.

“I was like, all these people have sacrificed for me to have the opportunities and go to these privileged environments and I also realized in a lot of ways how much it was a roll of the dice that I had ended up at these schools, and people who were just as smart as me, who worked just as hard as me, who were just as poor as I had been – did not end up having those opportunities,” Chambers Armstrong continued. “I think once you realize a lot of your opportunities are a lucky roll of the dice, it’s really hard not to feel compelled to even it out by paying it forward.”

After law school, Chambers Armstrong moved to Louisville, Kentucky, obtaining a fellowship to work with low-income domestic violence survivors. She drove around the state, a one-woman law firm out of the back of her car, representing women who could not afford attorneys in domestic violence proceedings.

Life Altering Tragedy

Following her two-year fellowship expiring, and laden with debt from law school, she went to work for a Louisville law firm for about a year before tragedy struck. Chambers Armstrong’s mother died in a traffic accident on the interstate on the way to Louisville to visit her daughter in 2019, who was five months pregnant at the time.

“I remember what struck me is that my mom had just reached this point in her life where she had retired,” she said. “She and my dad were building a house to be closer to me and their soon-to-be grandchild and they had all these plans that they were finally getting ready to realize, and then in just the blink of an eye it was all gone.”

Soon after losing her mother, Chambers Armstrong says she was moved to realize her own dreams. With an infant at home, she took a leave of absence from the law firm she was working at and launched a campaign for the metro council.

“If you want to make a difference if there’s something you want to do, you need to do it now, you never know what’s going to be on the horizon,” she said.

Shaping Policy

All of her experiences, growing up poor in rural Kentucky, working with poverty-stricken domestic violence survivors, and receiving government help are now shaping the policies and ideas for Louisville.

The “biggest issue” for Louisville is affordable housing, that’s why her first ordinance was aimed at dealing with the issue from the perspective of keeping people in housing.

“Everything that you care about can be tied to the lack of affordable housing,” she said, adding that domestic violence survivors struggle to leave abusive relationships because of the economics of housing and children often bear the health brunt of environmental concerns due to poor quality of what is available.

Low-income people, Chambers Armstrong said should have the ability to live close to where they work or wherever they want to live. She’s trying to move away from clustering low-income housing in impoverished communities. There’s an idea before the council to draw up a plan for accessible housing across Louisville, using America Rescue Program funding.

As an overwhelmingly white, wealthy district Chambers Armstrong is trying to figure out how to kick-start the conversation around equity and inclusivity.

“We shouldn’t be the loudest voice on this… but how do we start the conversation about being good allies, being good advocates, being followers as opposed to leaders,” she said, adding that specific infrastructure improvements may not happen in district 8 this year as dollars head towards areas of larger need in the city.

There is also a want from the councilwoman to see universal pre-kindergarten in Louisville. As a mom of two kids under two years old, she brings a perspective that had been missing to the metro council.

A Second Book in the Works

With the publication of Hill Women during the metro council campaign, Chambers Armstrong forgets that often constituents may have read the book, know a lot about her and what she thinks, believes, and worries.

She’s working on a second book called ‘Mom Out Loud,’ with state Rep. Josie Raymond, D-Louisville. The book seeks to dive into the idea of women participating in public life either before they have kids, or once the kids are teenagers or older.

“Families with kids under 18 are 40 percent of American households, but mom’s teenagers or younger are only 6 percent of Congress, and there are more former prosecutors and people born outside of the United States in Congress than there are moms with teenagers or younger in the household,” she said.

The idea is still being fleshed out, but the book is meant to be a call to moms of young kids to participate in public-facing decision-making.

Larger Ambitions?

Chambers Armstrong intends to seek a second term to her council seat, she enjoys the local issues and the effect that local politics can have on constituents’ daily lives. However, she does not want to be someone who stays in the seat for decades.

“It’s really easy to get complacent and I want to run at it with my best ideas and all of my energy and all of my enthusiasm, and then who knows,” she said.

“I think whenever you put yourself in this role of saying I want to be people’s voice, that’s a really big commitment, because you’re the only voice they have at that level, so it has to be your priority all of the time.”

Login

Login  Must include at least 8 charaters

Must include at least 8 charaters